via Iconic Photos

London Blitz: December 29th 1940

Seventy years ago, the Germans started the Blitz more or less out of frustration, without clear planning, as a sequel to the Battle of Britain. During the first half of the summer of 1940, the Luftwaffe focused on dominating British airspace, in preparation for a possible landing, and its bombardments were limited to airfields and other military installations. On 24th August, more or less by accident, a pair of Stukas dropped the first bombs on central London. Churchill seized the opportunity, and in ‘revenge’, 80 RAF bombers pounded Berlin. Hitler was infuriated. Nearly 600 German bombers came back during the next two weeks to bomb English cities, factories and airfields.

Then, at 5 p.m. on 7th September, the first major attack on London began. On that sunny afternoon, 348 Luftwaffe bombers crossed the English Channel, and for the next two hours ignited the city with incendiary bombs, the docks being their primary target. That same evening, the Germans were back, raining 625 tons of high explosives on working class neighborhoods in the East End. The Blitz went on for 57 consecutive nights and then spread to other cities in the U.K. In ‘Second Great Fire of London’ on the night of 29th December 1940, nineteen churches, thirty-one guild halls and all of Paternoster Row, including five million books went up in flames.

By the time the Blitz ended (as Luftwaffe diverted its planes east for the attacks on the Soviets) on May 16th 1941, more than 43,000 people had died in the strategic air raids. Writer Harold Nicolson compared himself to a prisoner in the Conciergerie during the French Revolution: “Every morning one is pleased to see one’s friends appearing again.” Yet, the English, being the English, just got on with it stoically. In stubborn, indignant fashion, the life went on. A survey taken during this period found that weather had a greater impact than air raids on the day-to-day worries of many Londoners. In his magisterial history The Blitz: The British Under Attack, Julian Gardiner observes, “egg rationing produced more emotion than the blitz.”

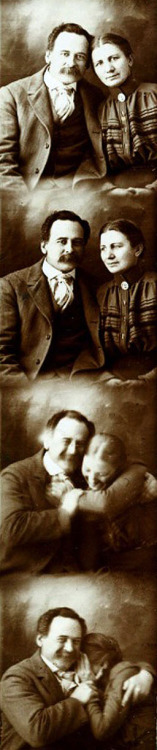

Thus predictably, most well-known of the countless photos taken during the Blitz did not depict carnage and chaos, but rather an extraordinary tale of survival and defiance. The above photograph featured on the front page of the Daily Mail, captioned as ‘War’s Greatest Picture’, was taken from the roof of the same newspaper’s Tudor Street offices by Herbert Mason two nights before (on 29th December). St. Paul’s Cathedral was surrounded not only by fires and smoke that fateful night, but an incendiary bomb did drop inside the Stone Gallery. During the Blitz, the importance of the Cathedral was so much so that Churchill insisted that if the church were to be bombed, all fire-fighting resources be directed there, and that “At all costs, St Paul’s must be saved.” The Daily Mail echoed this sentiment in the text accompanying the photo that the image is “one that all Britain will cherish – for it symbolises the steadiness of London’s stand against the enemy: the firmness of Right against Wrong”. To that effect, the editors at the Mail decided to crop the photograph quite liberally, to take out the gutted remains of houses in the foreground.

Interestingly, but not surprisingly, the photo was telling quite a different story on the continent within days. The Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung announced that “Die City von London brennt!”, and gleefully informed its readers that the conflict with England too was approaching its endgame. For Germans, the photo, with the blazing foreground ruins included, depicted nothing more than the centre of “britischen Hochfinanz” burning in London’s biggest blaze since “Jahre 1666″. Photographs never lie indeed.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=4da98443-e75d-4ee2-aacf-f732caaf65a2)